Q1: What is a Kokeshi?

A: Original Kokeshi were a wooden doll made by turn at hot spring resorts in Tohoku (northeastern Japan) as a toy for girl.

Q2: Who made the Kokeshi?

A: The craftsmen who lived around hot spring resorts. Their main products

were wooden bowls and round servers. The craftsmen were known as Kiji-shi

or Rokuro-shi (Woodturner).

Q3: What does the word "Kokeshi" mean?

A: The name of the wooden dolls varied from place to place. They were known as "Kideko" in the Fukushima area. "Ki" means "wood" and "Deko" means puppet. They were known as "Kibouko" in the Miyagi area, "Ki" means "wood" and "Bouko" or "Houko" means "stuffed doll". "Kokeshi" is what they were called in the Sendai area. "Ko" means "wood" or "small" and "Keshi" is short for "Keshi-ningyo, which were small terracotta dolls made around Sendai. The word "Kokeshi" was chosen as the general name of these dolls by the Tokyo Kokeshi Collectors Club in 1940. The common meaning of the names are "small wooden doll".

Q4: I know there were various Kokeshi craftsmen, however where were kokeshi first produced?

A: It is not known. Although, it is believed that they were first produced in Tohgatta, the east side of Mt. Zao, in Miyagi Prefecture. They are thought to have been created during the Bunka-Bunsei (1804 - 1830) in the Edo Era.

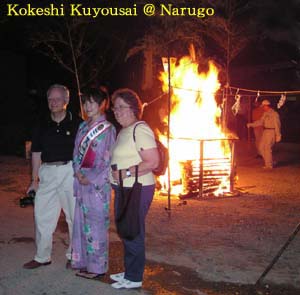

Other places, namely Tsuchiyu in Fukushima Prefecture, Sakunami and Narugo (Naruko) in Miyagi Prefecture also started to produce Kokeshi in Tenpo years (1830 to 1844) respectively.

Q5: Does the shape of Kokeshi vary based on where they are made?

A: There are common characteristics. All have spherical heads and cylindrical bodies, with no hands or legs. But there are various shapes and designs depending on where they are made, and those variations are aligned with their phylogenetic history. Those variations are categorized into 10 or 11 groups. These groups are Tsuchiyu, Yajiro, Tohgatta, Zaotakayu, Hijiori, Sakunami, Naruko, Kijiyama, Nanbu, and Tsugaru. Some specialists separated the Yamagata and Sakunami into separate groups, making 11 groups.

Q6: Were these groups also recognized when Kokeshi were first being crafted, the end of Edo Era?

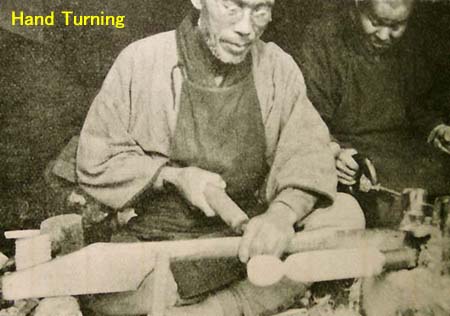

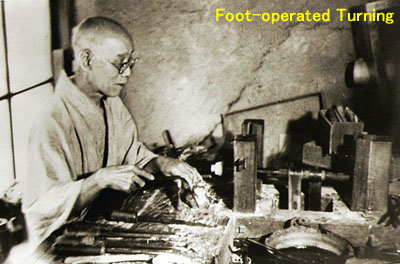

A: No. Originally, there were thought to be 3 groups, Tsuchiyu, the East side of Zao Mountain, and Naruko. The innovation of the foot-operated lathe in 1880s Tohoku accelerated the diversification of shapes and designs. Before this, all lathes were hand operated, which required two people to operate, the carver and the turner. With this innovation, a single craftsman could carve by hand and operate the lathe their foot.

Tohgatta and Aone (another hot spring located 7 km west of Tohgatta) were the centers of this innovation in Tohoku. Many craftsmen went there to study this new technology. It was a school of sorts, and they learnt not only foot-operated turning but also how to use new chemical dyes. They produced “Kokeshi” with yellow, green, purple on top of the original black and red.

Tohgatta and Aone (another hot spring located 7 km west of Tohgatta) were the centers of this innovation in Tohoku. Many craftsmen went there to study this new technology. It was a school of sorts, and they learnt not only foot-operated turning but also how to use new chemical dyes. They produced “Kokeshi” with yellow, green, purple on top of the original black and red.

Also, they began using their lathe to apply paint, and they produced various spiral and ring patterns. They had never tried to paint using hand turning, since two people painting was inefficient.

This change encouraged craftsmen to bring out their own originality, and

accelerated the diversification of shapes and patterns. The craftsmen greatly

enjoyed heir time studying. They went back their home hot springs and started

to produce their own styles of "Kokeshi". Because of this, the

10 or 11 groups were established in the 1890s.

Photos of the 10 Phylogenetic Groups.

Q7: What were the "Kijishi", Kokeshi craftsmen, like?

A: The Kokeshi was born at the end of the Edo Era, but the history of woodturners, called "Kijishi", is much older. The first woodturners in Japan were immigrants from the Silla Kingdom in Korea, who came to Japan in the 4th or 5th century, as one of retainer group of the Hata family alongside other groups of retainers. These included sericulturists, weavers, potters and so on. The woodturners established their base in the mountainside east of Lake Biwa, and launched their production. One of their well-known activities was that they produced wooden stupas, the three-storied pagoda stores the Darani sutra, in 770 A.D., some of which still exist in the Horyuji Temple. Even now, some woodturners continue to work to the east of Lake Biwa. Such craftsmen include Kimigahata and Hirutani, in the Eigenji Oguradani Kanzaki district in Shiga Prefecture. Their group is believed to be the origin of the term "Kijishi". There was a shrine known as Taikokijiso Shrine (also known as the Tsutsui Kumonjo) in this village, which presided over all "Kijishi" families in Japan.

Q8: What kind of authority did the Taikokijiso Shrine have?

A: With the passing of the years, many branch families of "Kijishi" spread from Shiga of east Lake Biwa to most of all mountains in Japan which had good materials of wood, and they produced wooden bowls, round servers, and semi products for japan ware. And they were still shrine parishioners of Taikokijiso Shrine and many of them had the same family name of "Ogura".

Taikokijiso Shrine (or Tsutsui Kumonjo) had a very unique system, which was called "Ujiko-gari". This Shrine gave woodturning licenses to "Kijishi" in return for annual licensing fees. The license gave the guarantee that "Kijishi" would be allowed to cut any wood that is growing over 4/5 the height of any mountain. The government of each Era also recognized this license. But there was one issue, and it was how to collect the annual fees from the "Kijishi", who were spread all over Japan. Many had moved from mountain to mountain in order to get good raw materials.

"Ujiko-gari" was the system used to recover the license fees from "Kijishi". The priests of Taikokijiso Shrine went around all of Japan periodically and made records of the "Kijishi" to collect the fee. If new a branch of family sprang up, the priest provided a new letter of license (called "Kijishi Monjo") to this family.

This system was decommissioned during the middle of the Meiji Era, after operating for several hundred years. The operation documents of "Ujikogari-cho" still exist, and are evaluated as very valuable historical sources to follow the "Kijishi" movement.

Q9: What kind of authority did the Shrine have? "Kijishi Monjo" sounds very important for "Kijishi", isn't it?

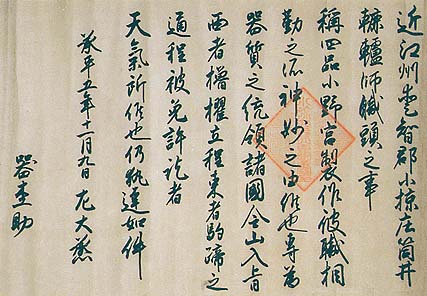

A: Actually, the letter of license, which the peripatetic priest gave to

"Kijishi" was only a copy. Taikokijiso Shrine held all original

licenses, which were written by the past emperors, Suzaku (10th century)

and Ogimachi (16th century), permitted to cut any wood higher than 4/5

up any mountain. However, those original documents were also fakes.

A: Actually, the letter of license, which the peripatetic priest gave to

"Kijishi" was only a copy. Taikokijiso Shrine held all original

licenses, which were written by the past emperors, Suzaku (10th century)

and Ogimachi (16th century), permitted to cut any wood higher than 4/5

up any mountain. However, those original documents were also fakes.

However, the government of each Era, Nobunaga and Hideyoshi (16th Century), endorsed those licenses, and as such, these copies were officially recognized. This may be seen as the government protecting the industry.

"Kijishi" had conflicts with those who had previously settled in the areas, and these licenses helped "Kijishi" to avoid further disputes.

The attached photo is a copy of a license provided by the Suzaku emperor,

which was highly guarded by the "Kijishi" family.

Q10: Why was the system of "Ujikogari" decommissioned in midst of the Meiji Era? Did the "Kijiya Monjo" also become ineffective?

A: This might relate to the birth of Kokeshi.

"Ujikogari" itself continued to be conducted throughout the middle

of the Meiji Era (1880s) as a formality, but by the end of the Edo Era

(early 19th century)the effectiveness of the "Kijiya Monjo" was

all but gone.

During those years, a series of bad harvests and famines struck, and the conflicts to utilize mountains between settled people and the "Kijishi" escalated. As such, the government could not keep protecting the woodturning industry.

Several cases were brought before the court, but results were not in favor of the "Kijishi".

"Kijishi" craftsmen who lost their privileges in the mountains had to go down to nearby village of settled people and accept their rules and practices. The hot springs, which were located in the mountainside, were the best places to settle for "Kijishi", and they tried to continue their woodturning works in those places. Some original settlers in these hot spring learnt turning skill from the "Kijishi", and started to produce simple toys.

Q11: How did the settlement of "Kijishi" relate with the birth of Kokeshi?

A: It is said that the following three conditions led to the birth of Kokeshi.

- "Kijishi" came down from the mountain and settled around hot springs. This meant that direct contact with customers became possible, and "Kijishi" captured the customer's demands and preferences more readily..

- "Kijishi" learnt "Akamono".

- Recreation practices in hot springs for peasants were established in the Tohoku district. Those practices were a kind of re-birth process to recover the power of a good harvest..

Q12: What was "Akamono"?

A: "Akamono" is a kind of toy, colored with red dye. Red was believed

to have magical power to protect against smallpox. Many parents purchased

"Akamono" toys for their children.

Major places of production of "Akamono" toys were Odawara and

Hakone. Spinning tops, Daruma, and nested dolls with red paint are good

examples of "Akamono" toys. Shichifukujin, 7 layered nested dolls,

were well known toys from Hakone and they were based on Russian Matryoshka

dolls. "Akamono" toys had spread to Tohoku by the end of the

Edo Era (early 19th Century). During this time, in Tohoku, it became common

to make pilgrimages to the Ise and Konpira Shrines. Odawara and Hakone

were on the road to both shrines, and some of pilgrims got "Akamono"

toys there and brought them back to Tohoku.

Many peasants who went to hot springs liked to get "Akamono" toys there. "Kijishi" started to make them in response to customer demands.

Q13: Could you explain why "Akamono" was so important?

A: Originally, "Kijishi", only made bowls or round servers, and they never imagined putting color on them. Of course, they also made some Japanese ware, but the lacquer painting was done by another group of craftsmen. They believed "Kijishi" should carve the wood, and never touch dyes. Therefore, it was a big change when "Kijishi" colored their products with dyes. And this was the first step to Kokeshi production.

Q14: Do you think that the recreation practices in hot springs were also started at that time?

A: Yes, as for peasants or common folks. However, it's recorded that aristocrats and feudal lords began visiting hot springs starting in the 8th century.

Q15: How were the hot springs for peasants in Tohoku?

A: Peasants stayed at hot springs for 3-5 weeks, between rice harvests. They brought pots, pans, futons, and other articles to the hot springs, and cooked their own meals at self-catering accommodations. Of course, their main goal was to relieve fatigue, and the hot springs were perfect for that. However, they also tended to feel that their grain productivity was also recovered during their time at the baths. They believed the spirits of the mountains had powers regarding grain harvests, and mountainside hot springs would be the best place to receive those powers. This means the hot springs were not only for physical effects, but also spiritual. It is said that the hot spring care were regarded very similarly to a religious ritual of re-birth, and that the baths were seen as the womb of the mountain.

Q16: OK! If so, why did such peasants need the "Kokeshi" as a souvenir?

A: The Japanese word for souvenir is "Miyage". Etymologically, "Miya" means "shrine" and "Ge" means "something given by a Holy One". So, "Miyage" were seen as a physical blessings of the gods, such as power, good luck, health, long life, and so on, received at a shrine or holy place. "Kokeshi" were a similar concept to "Miyage", and peasants who got the blessing of grain productivity, had to bring "Kokeshi" back to their village. "Kokeshi" were a symbol of this blessing, and also carried this power. "Akamono" toys also had similar characteristics, due to the magical powers held by the color red. "Kokeshi" were seen as the best symbol of power granted by the mountain spirits.

Q17: Could you tell me why the "Kokeshi" was symbolically the best?

A: This question requires a very long answer. You can visit the following 3 pages, however those pages only have Japanese versions. Those pages explain that: 1. "Kokeshi" as used as a wand, 2. Symbolism of flower pattern, and 3. Symbolism of spiral pattern. Those symbolisms emphasize the expectation that Kokeshi carried the blessings of the mountain spirits.

Q18: Kokeshi were used as wands? What do you mean by that? (MK-san)

A: I am often asked why Kokeshi do not have hands and legs. The discussion

for "Kokeshi" as wands provides the answer to this question.

One important characteristic of the wand, is that they are the accouterment

of a person who comes and goes across different boundaries, including the

spirit world, and social castes.

Here are several examples of such from across the world.

- Hermes has his wand, Caduceus (Kerykeion) : Hermes can pass the boundaries into the underworld, to the land of the dead. He would then bid the souls of the dead to pass on.

- Arlecchino has a sceptre: Arlecchino, comic servant characters from the

Italian Commedia dell'Arte, can pass through the boundaries of social classes.

In some cases, he belongs to both the upper, and lower classes in Bergamo.

(Reference: The Fool and His Sceptre: A Study in Clowns and Jesters and Their Audience. Author: William Willeford) - Itako, a Japanese shaman, has Oshira-sama (stick shape as a puppet): Itako can act as a medium of the dead, and this means she or her puppet can come and go down to the nether world.

- Other examples:

・ Orchestra conductors have a leading staff: world of art, may belong to the area of God d

・ Witch has a broomstick: magic kingdom

・ Police have batons: good and evil